A World Without Words

Longread. 2000 words. Reading time: 6 minutes

Left Kees. With sister and brother and Uncle Jan. On the Doornseweg, Leusden.

The Leusderheide

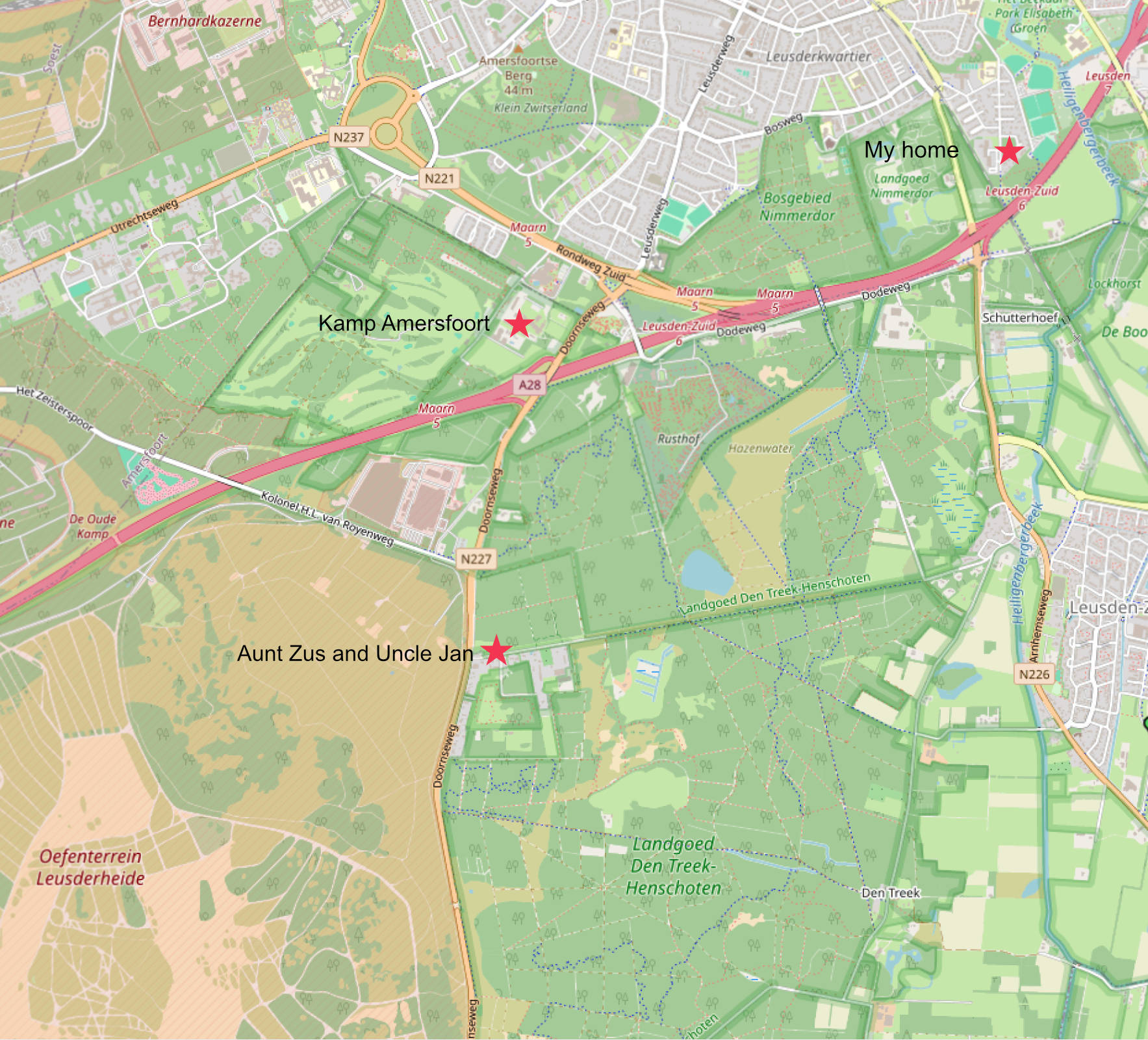

The first two years of my life I spent on the edge of Den Treek, opposite the Leusderheide. We lived in a farm of ‘Tante Zus and Ome Jan’, who rented the front part to my parents. Later my parents moved to Rotterdam, where I grew up. I was six years old when my sisters got scarlet fever. To prevent further infection, I was sent, schoolbooks and all, to Tante Zus and Ome Jan. I can still remember the very autumnal and dark weather of that time.

Middle: Kees. With sisters and mother. Doornseweg Leusden.

Since then, my parents sent me to Leusderheide every summer. I stayed there for many weeks every year, until I was eleven. I was always alone there; there were no playmates. I can’t remember ever being bored there. Being ‘alone’ seemed to suit me well. In addition, my parents had the habit of moving very often. Always a new schoolyard, where I always felt like an outsider.

In the early evenings I crossed the Doornseweg to go to the shooting ranges on the Leusderheide, looking for empty shells and bullets; that was still possible then. During the day I often wandered through the forests of Den Treek. Alone. I regularly walked four kilometers from the Leusderheide straight through Den Treek to Zuid-Leusden, where another aunt lived. Alone. Nowadays, there would be no parent who would let their eight-year-old child walk through the forest alone! At the time, that seemed to be quite normal. Apparently, people trusted the world.

That ‘alone’ wandering through the woods also meant that there was no one to tell me what everything was called. No one named things, no one gave the trees, plants, animals and phenomena a name. Everything was as it was. No labels, no words were pasted on anything. Words that cover things up, creating a distance, darkening them and killing the magic.

Later in life I began to realize the impact that had on me as a person and my persona. I came to the simple discovery – or rather, the realization – that there is nothing, absolutely nothing in the universe that has given itself a name. The world itself is completely wordless . It is man who gives things his own namearbitrariness. If I want to experience my world as it is, all words will have to disappear. And they do disappear regularly, really! There are people who call such an experience ‘magical’ or ‘spiritual’. For me it means that the world finally becomes ‘ Real ‘. That can be enlightening, fascinating, but certainly also terrifying and confusing. Psychoses were not foreign to me. A world without words is also a world without history; at that moment there is only the event.

The Lens on Nature

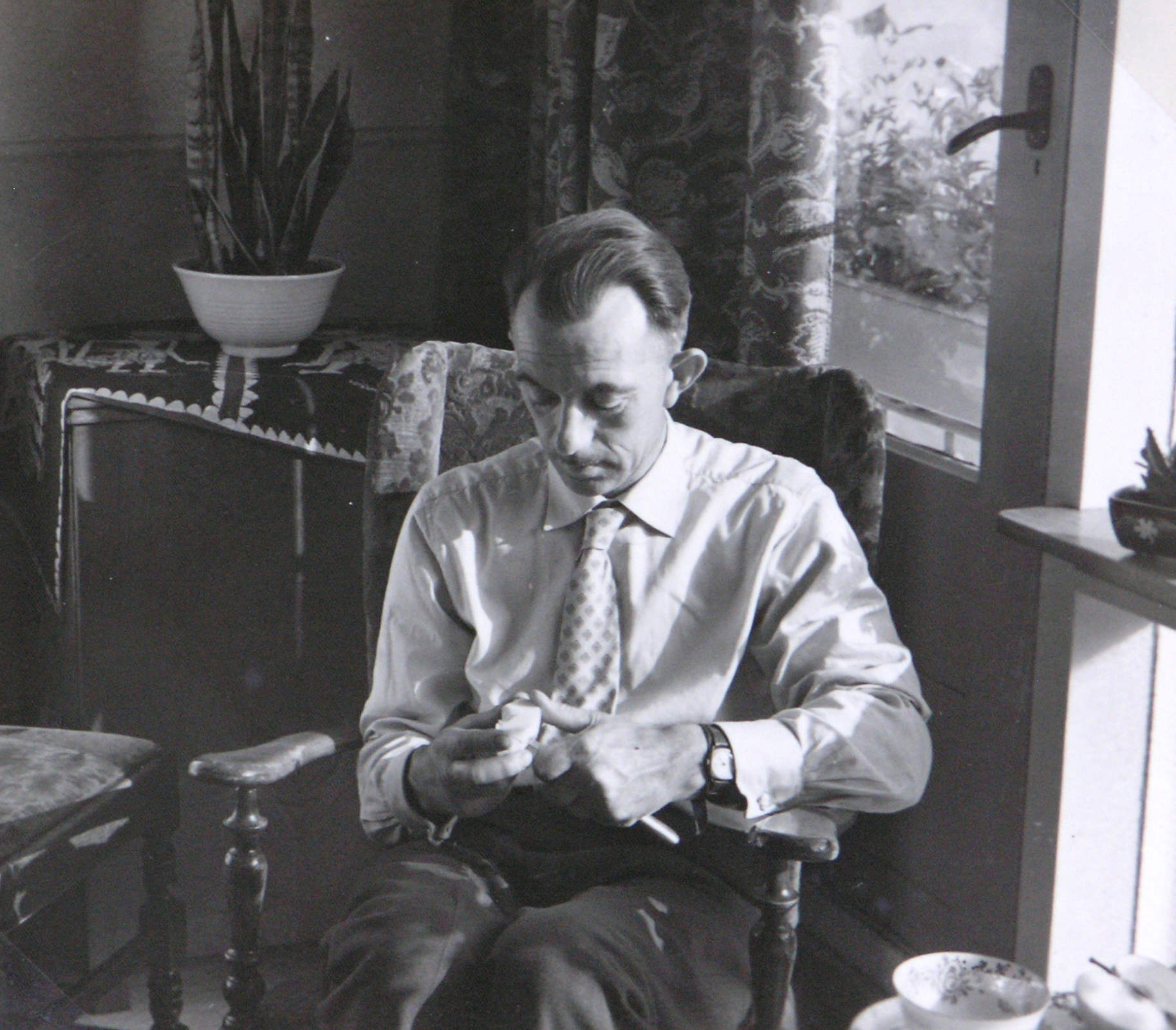

My father on a motorcycle. (1938)

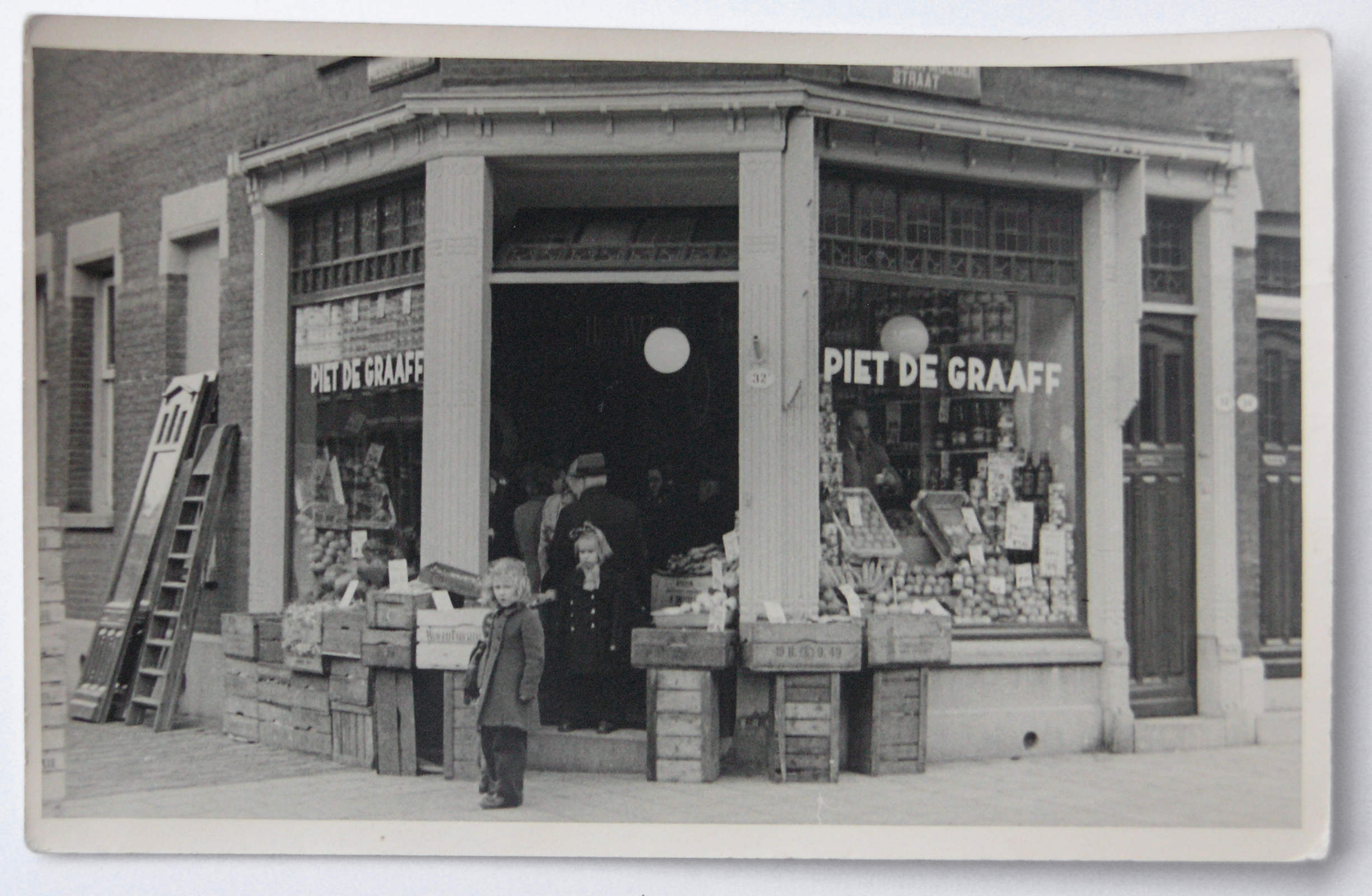

My father’s vegetable shop. Gerrit Jan Mulderstraat. Rotterdam

My father was a potato, vegetable and fruit trader, or greengrocer. And he was successful, because he had several shops. I don’t know exactly whether he was a show-off in his younger years, but he certainly bought the most expensive things, including a Eumig C3 super 8 film camera. He also bought a fancy camera for my mother: a 6 x 6 camera, Zeiss Ikon Ikoflex. Not quite a Rolleicord, but still. As far as I know, my mother never took a single photo with it.

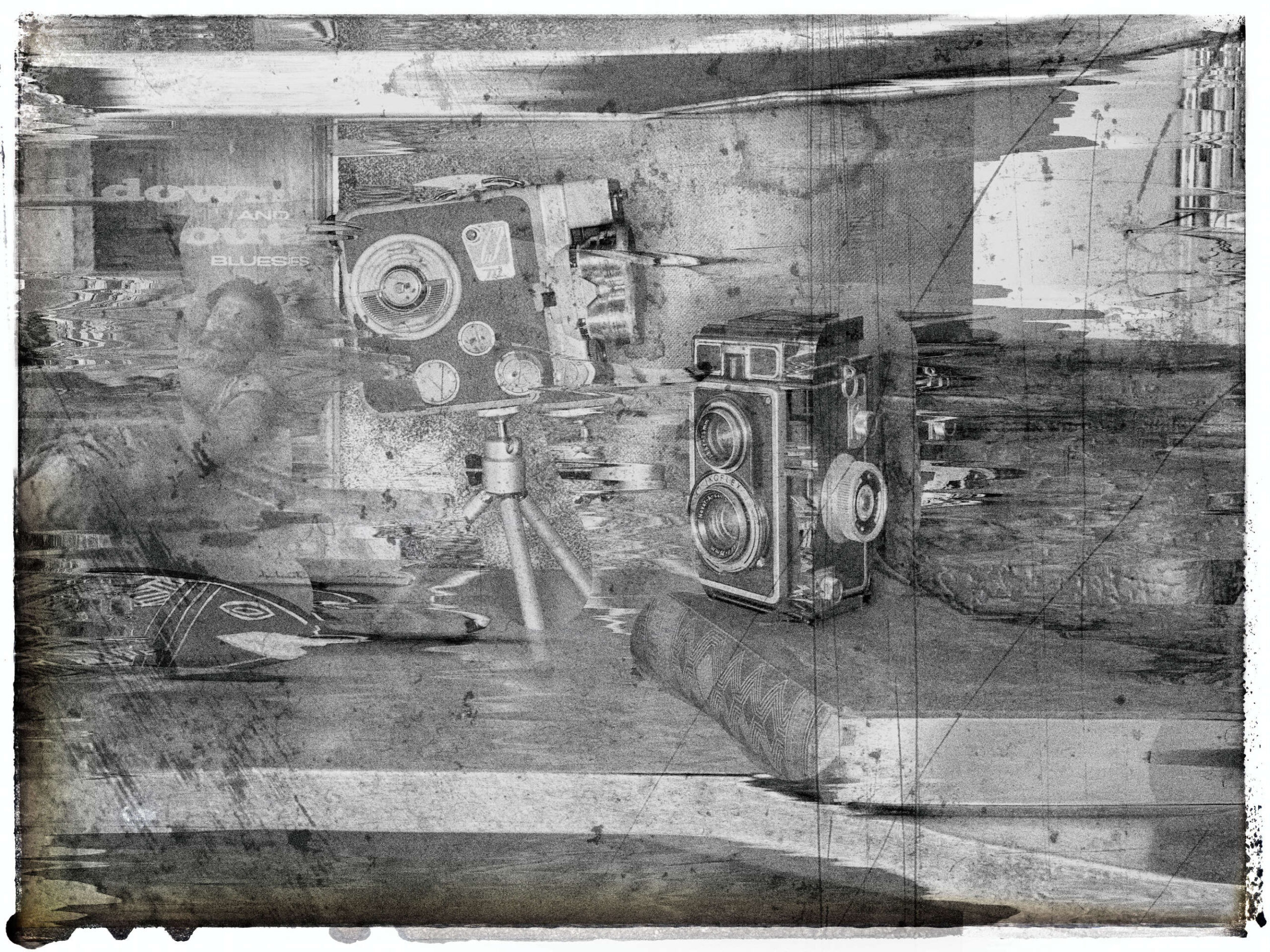

Still life with my parents’ cameras.

At the age of twelve I started playing with that camera . And immediately won the first prize in a photo contest at the Marnix Gymnasium in Rotterdam. Later I really started taking pictures, especially a lot of trees in the Kralingse Bos. When I was 17, I had an exhibition at the Melanchton Lyceum and sold my first photo to Mr. Visser, vice principal of that school. A photo of trees of course. I should also mention that my father owned a very thick photo encyclopedia, great; I could get lost in it for hours. (Encyclopedia for photography and cinematography. Elsevier. 1959 Amsterdam).

Nature photos. 1968. Archive is badly damaged.

In 1968, as a seventeen-year-old, I entered the Sint Joost Academy in Breda. At the time, it was the only academy for visual arts in the Netherlands with a photography department. The first trimester, I still took photos of trees and nature, after that everything changed. Fashion, architecture, still life and reportage photography. We had a different teacher for each genre. That was a good learning experience. My great heroes at the time were the young Richard Avedon, Alfred Stieglitz and especially Edward Steichen. But also Elliot Erwitt, Guy Bourdin, and so on.

I didn’t come into contact with trees and nature again until I ended up on Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Territory, Australia in 1974. An aboriginal reserve; no white Australian could or was allowed to go there, it was completely protected. But there was mining there and work had to be done. You could only get to that island with a special work permit. I worked there in construction for a metal and construction company.

Dancing boys. Angurugu.Groote Eylandt. Northern Territory. Australia.

Mijn kennismaking, mijn confrontatie en ervaringen met die aboriginal cultuur was verpletterend. Het heeft me decennia gekost om dat te verwerken. Ik kwam pardoes terecht in een volkomen non-literaire cultuur. Waar mensen een voor mij onbegrijpelijke, doch zeer intense, verbondenheid hebben met de wereld en natuur waarin zij leven.

Ayungkwiyungkwa Beach. Groote Eylandt. Northern Territory. Australia.

‘The Spirit of Tommaso Cassaio (Masaccio) Arrives. (At the Holy Tree of the Emerald River)’.

We in the West may have many monuments, cathedrals, museums and other heritage – none of that was on Groote Eylandt. Yes, there were Holy Places. But really Holy, because even the Australian police were not allowed to enter those places. I visited those Holy Places. And what did I see? Nothing, just nothing. At least to my feeling. It was just a place, with rocks and trees. In a certain confusion I tried to capture that. When I reached the Emerald River early one morning with my Yamaha dirt bike, I was deeply moved by the beauty and mysticism of a tree. Later, in 2005, I tried to visualize that experience in a work entitled: ‘ The Spirit of Tommaso Cassaio (Masaccio) Arrives. (At the Holy Tree of the Emerald River)’ .

In 1977 I returned to the Netherlands to study visual communication at the Rijksacademie. Since then I have photographed everything except nature, forests and trees. No, that only started to pick up again when I moved with my family to Hoogland in 1999, a village just above Amersfoort. Close to the Utrechtse Heuvelrug, close to my Den Treek. But in all those years before that, when I worked in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, I regularly got in the car and went to Den Treek and the Leusderheide. To relax or to ‘park’ my depressions there. Den Treek always attracted me; it was the only sensible place for me to vent my soul.

A shadow from the past

What does it mean to be a child? I have seen it with my own three children. The first seven to eight years they live in a magical world. They think spontaneously, circularly and spatially. But once they are at school, this is quickly put to rest. The sounds they utter impulsively suddenly appear to be ‘words’. And then they have to be put in order. In other words, they learn to read, write and calculate. This means that spatial and circular thinking has to make way for linear, rational thinking. Whereby the magical world disappears like snow in the sun. And when they are adults later, they have to follow courses and therapies to find out who and what they really are. Sigh.

The Meent in Rotterdam

Jewish boy. Warsaw ghetto.

I must have been about five years old when I was roaming the Meent on my moped on a sunny morning. Back then there were only shops and shops. (Now there are only restaurants and eateries). At one point I stopped at a shop that had all sorts of books on display behind the window. On the cover of one book was a photo of a boy my own age, with his arms up. I don’t remember how long I stood there staring, but it made an indelible memory and impression on me. No matter how young I was. I don’t think I had any idea what a book was. Nor did I have any idea what a photo actually was. I mirrored myself with that boy in that photo. I can’t say anything else about it. It wasn’t until thirty-five years later that I discovered that the photo on that book was a crop of a photo of the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw.

My Father’s Bookcase

Een berg brillen in Auschwitz.

I must have been about fourteen when I pulled a book from my father’s bookcase. I took it upstairs to my bedroom and study in the attic. In that book I saw all sorts of incomprehensible pictures: big mountains of shoes, mountains of suitcases, mountains of glasses, then a picture with running naked women, an immense pit with all kinds of naked dead people. And so on, and so on.

At that age I had no knowledge of the Second World War, let alone the Holocaust. No, that came many years later. My father never told me anything about that book; we never spoke about it. And later that book suddenly disappeared from his bookcase. My father was a very religious man, active in the reformed church system. Only later in life, during the war in Yugoslavia in the nineties, did he abandon his faith. And my mother had to go to church alone.

The silent witnesses

Kees and uncle Jan in his vegetable garden. Doornseweg, Leusden.

As I wrote, I spent many summers in my youth on the farm of Aunt Zus and Uncle Jan. They were very silent, quiet people. I cannot remember that they told me a single story or anecdote. Every evening Uncle Jan silently rolled 30 cigarettes for the next day. He was a postman and maintained a large vegetable garden.

Aunt sister visiting us. Admiraalsplein, Dordrecht.

Uncle Jan visiting us. Pannekoekstraat, Rotterdam

That silence only became meaningful to me when I visited Camp Amersfoort for the first time in 2005. Only then did I realize that Uncle Jan and Aunt Zus lived one and a half kilometers away from Camp Amersfoort during the war. Would they have known, or had knowledge, of what happened there in that Camp and the surrounding area? And not only in the Camp, but also on the Leusderheide, opposite where they lived? I think that must have been the case.

My Biotope

Locations.

Since 2012 I have been living at the southernmost point of Amersfoort, far from the hustle and bustle of the city centre, which I don’t really get involved with. I now live next to the Lockhorsterbos, which borders Den Treek. No, I don’t visit Kamp Amersfoort every year. I do spend a few times a week in Den Treek, either walking or on my mountain bike. And I still discover new mysterious places there that amaze and surprise me. The forests have still not given up their secrets, which perhaps never will. And perhaps that’s just as well…

I experience the forests here as my natural habitat. I enjoy them intensely, their power, their splendor and their beauty. But I will always calmly observe Armando’s warning:

The beauty should be ashamed.

And not to forget the beauty of the places where the enemy perished. Beauty no longer knows what to do because of madness. Beauty is out of balance.’

Armando. Diary of a perpetrator (Amsterdam 1973)

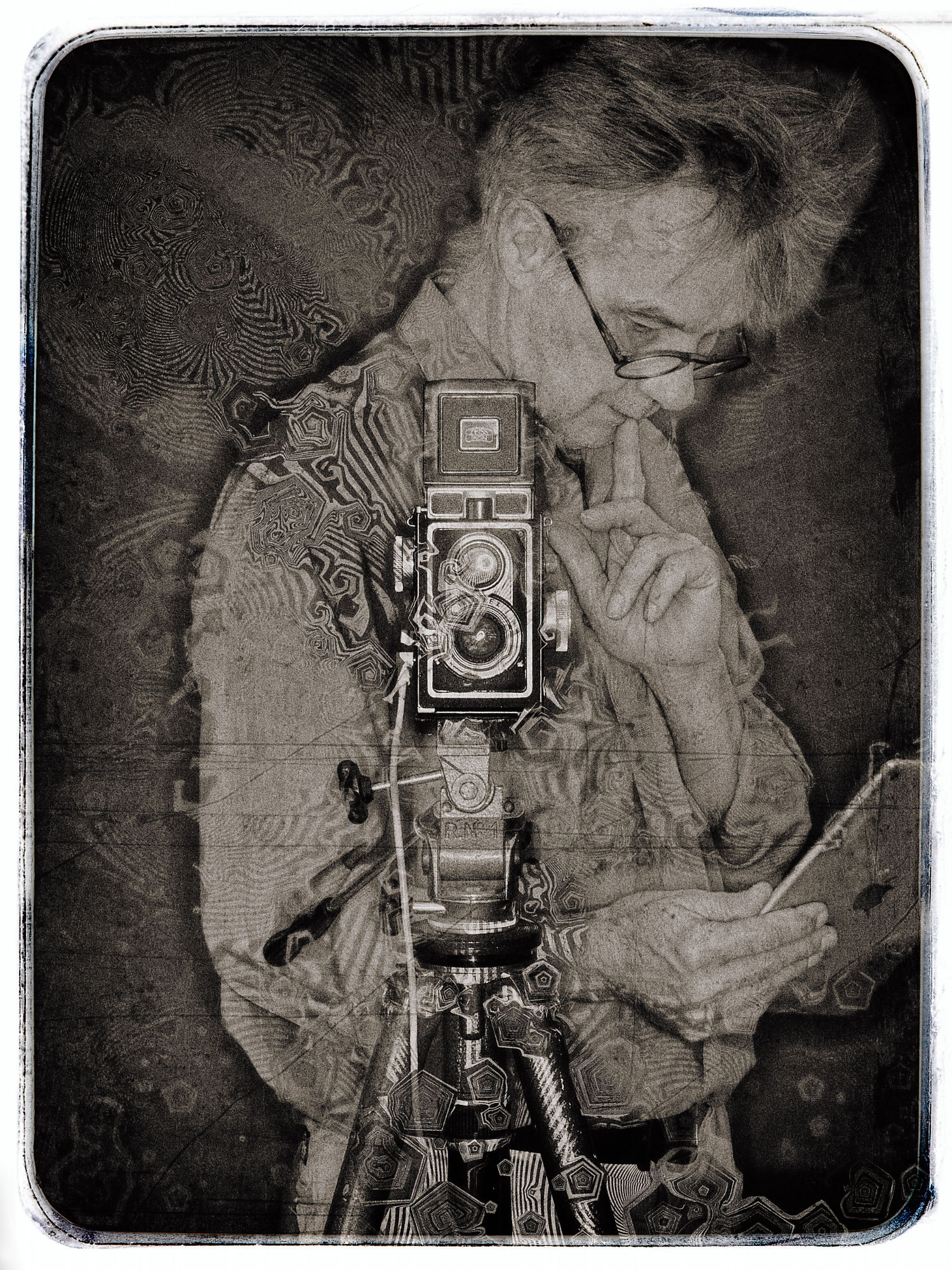

Self-portrait. 2017.

Kees de Graaff. June 4, 2025 . De Eemgaarde, Amersfoort.